Recently, a friend and former colleague asked through LinkedIn what people would strive to improve on if they were 181. Having recently turned forty and being away from the classroom for two years, I am perhaps a little disconnected from today’s youth. My first answer appears boring: reading, writing, focusing. But there is more.

This is a fascinating question. I will answer in three parts.

First, we should also be asking 18-year-olds. And 25-year-olds (what would you wish you could have gotten better at when you were 18) and 14-year-olds (what do you think you should be getting good at).

I asked an extremely bright, amazing, and inspiring twenty-two-year-old. She said:

Projects were too structured and layered, which radically limited creativity. She thinks that rather than following a series of requirements she felt that schools should create opportunities to develop creativity.

Secondly, she argued that young adults do not “know how to self-regulate” and the “the process by which you get to know yourself” and become able to “take care of yourself.”

Second, the question may be too hard. I reckon I know what he was looking for, but what I think I should get better at and what I should get better at can be misaligned. Besides, answering that question, I believe, requires thinking about other questions first.

I love these from Neil Postman, and I think they are a good start to answer the question.

What do you worry about most?

What are the causes of your worries?

Can any of your worries be eliminated? How?

How would you decide which of these worries to address first?

Are there other people who share the same worries?

What bothers you most about adults? Why?

What, if anything, seems to you to be worth dying for?

What seems worth living for?

How can you tell the good guys from the bad guys?

What would you like to be doing five, ten years from now? How can you get there?

What do you think are some of man’s most important ideas? Where did they come from?

What is progress?

These questions are clearer, and answering them helps understand the first question. Where I see myself in ten years helps me see which steps I should take. Examining what causes anxiety to myself, my peers, and others, and thinking about how to prioritize, helps crystallize existing challenges. There also needs to be an emotional component—we can only experience the world as we experience it. That sounds tautological, but it is worth remembering: we are embodied. Recently,

shared Husserl’s criticism about our standardization and quantification fetishism.This is what I would work on (if I were 18 and possessed my lived experiences and academic background). My big five are: reading, writing, focusing, resiliency, and living.

Reading

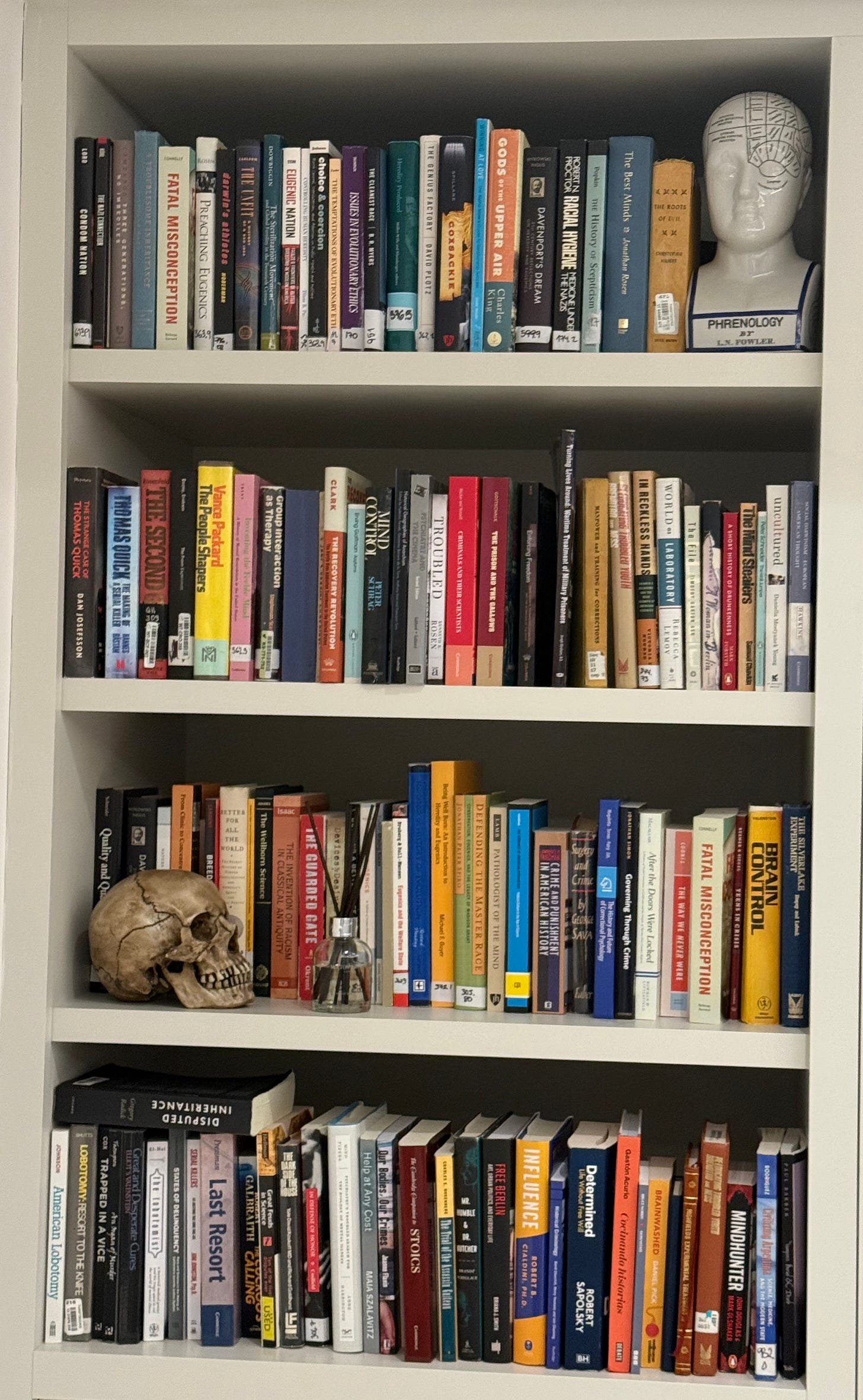

Engaging with written material is a great way to think deeply and thoroughly about something. Most, if not all, the essential questions are complex and require thorough engagement, and reading provides an unrivaled way to do so. In my experience, there is no substitute. There are several reasons to read. I’d highlight both rational and emotional ones.

Reading can help readers think through sophisticated technical subjects. The world, or at least our descriptions of it, is a complicated place. Most academic and technical fields have lots of nuance and caveats and open questions – there is no simple way to master them. The written word is an excellent way to explore these marvellous mysteries.

When I worked as a school leader, I tried to get a project started whereby we would post photos of teachers reading and a small paragraph where they explained what they were reading.

Living a meaningful life is another reason why reading is so critical. Humans seem to seek both agency and patterns in the world around them. Many of us are at one time or another angsty, bored, broken-hearted, cold, concerned, depressed, happy, loved, loving, scared, worried, and more. The best tools ever developed by humanity are preserved in some great works. Others, like Alain de Botton, have already pointed out that the point of literature is not the summary of facts but rather the medium. Perhaps, more importantly, reading allows us to ingest words.

Writing

Secondly, good writing is essential as a way to think through something.

We often misconstrue writing as a way to communicate something already clear in our heads, but when dealing with complexity, it helps the writer think through the issues. Some questions and phenomena are beyond mastery unless they are explored through writing.

Schools are mostly to blame for not helping people use writing to think. Most of the time, students are asked to write something so their teacher can see whether they have understood something the teacher already knew. These kinds of questions may include defining an electron or natural selection. In the social sciences, a student may be asked to explain Freud’s theory of dreams or discuss whether the alliance system caused the Great War. These questions are a valuable first step. Nevertheless, there are two fundamental problems.

The first problem is that these exercises are used to assess whether students know other people’s answers to other people’s questions. It negates the possibility that these thriving, curious minds have questions of their own. Rather than always answering other people's questions, we should strive to help our students derive their own questions and consider how to go about answering them.

The second problem is more complex. Most of these assignments are designed to assess whether the students have learned something. This means that teachers have to read whatever the students wrote. This means that we fail to teach budding writers how to engage readers effectively. The second challenge is that these valuable assignments misconstrue the purpose of writing: to think through something. I leave this excellent video about writing:

Focusing

Recent technological advances have created quick gratification loops, super-engaging short content, and added showmanship into the lives of young people. These technologies reward short interactions and swiftly move on to another engaging thing rather than focusing on something so we can appreciate its nuance and complexity. Lessons ought to be engaging and interesting, but often the most interesting parts of a subject require a deep engagement with the subject.

Each subject gets more riveting when you explore the nuances and intricacies of the topic at hand. This requires focusing on these rather than moving from reel to reel. Secondly, being a novice is difficult. Perhaps, as we get older, we forget how difficult a new subject or activity can be. Often, one needs to get over a learning curve to enjoy a subject or activity. With no focus, without the boring, repetitive bits, there is no payoff.

One of my great pleasures has been to teach wonderful young people. I’ve had students who, at 16, were better thinkers and writers than I was in my 20s. I did worry about their focus.

As I thought more about what my friend asked. As I drafted my answer to his post, I realized there were two other areas worth mentioning (as you can see, writing forces you to think).

Resiliency

Well-intentioned changes have robbed young people of the opportunity to fail. I’ve worked at schools where students could retake an exam as many times as they wanted.2 The fact is that the world is changing at an ever-increasing pace, and that we can no longer be sure that what you learn during a professional training degree will retain its validity throughout one’s career. New technological innovations are changing the working environment and professional landscape in unexpected and disruptive ways. The adults of the future need to be able to adapt, and that adaptation requires resiliency.

There are numerous ways in which schools can help young people become resilient. One of them is by challenging them intellectually, by posing questions that may make them emotionally uncomfortable, and by providing scaffolded opportunities to fail (or succeed). Schools are not only meant to be part of life, but are supposed to help students reach their goals, a vision that is often at odds with the actual practices of many schools. How can we expect a student to sustain themselves in the world outside if teachers have chased every missing assignment, if they have had little independence and autonomy? Being independent and autonomous are skills that demand practice, yet such schools seem to overzealously pursue short-term gains at the expense of their students' well-being.

Living

I am now forty, and I would tell my 18-year-old self to focus more on relationships. Each year goes faster, and it seems increasingly difficult to make new friends. When you are six, you can approach another six-year-old and ask if they want to play. If I approached another adult and asked the same question, it would be interpreted differently.

But there is more to this. There are all kinds of relationships that we would be richer for strengthening. This includes friendships, mentors, professional relationships, amorous relationships, and many more. We are social animals who thrive in communities.

Our modern world has made it easier than ever to migrate. I have lived in five countries and nine cities. Every time I have moved, I have lost friends and made new ones. We live in bigger cities where, in some cases, we may never interact with the same person twice. We have technologies that are meant to connect us, but may be replacing deep relationships with curated stories of ourselves.

Lately, I feel, like the most critical area an 18-year-old could improve on is developing a tool-kit through which to live a meaningful life. Whatever each individual may decide that is. We should provide them with opportunities to enrich themselves so that, despite all the woes, they can find each other’s light amidst the enveloping darkness of the universe.

I'd love to know how you would answer this question. Feel free to comment or perhaps DM me, and we can co-publish your answers, or I could collate answers into another post.

My friend is building a school and he was curious about the answer to this question because the school he plans to build promises to be better.

This is bonkers. I agree that not all students master the material at the same time. To some degree, I also think it does not matter when they do it. If they achieve an equal level of mastery by the end of the term, why report a grade that suggests they have not? On the other hand, I had a student get less than 10% on an exam four times before I was allowed to fail them for that exam!

Thanks Christian!

Without this post, I often reminisce what I would have done again as an 18 year old. I could have travelled to more places, lived abroad, taken a gap year before starting university.

This is why nostalgia is always so powerful to me. I often revisit my hometown and the place I grew up, because there's a part I never grew old.

And I could do with reading novels as a habit. I never picked it up as a child because as a second language learner, I really didn't like reading Dickens.