Today, I will feel pain.

There is one thing I know for certain: today I will feel pain.

I mean real pain– the kind of pain you wouldn’t wish on anyone, the kind of pain that makes it difficult to carry on. It doesn’t matter if today happens to be Christmas or my birthday. Unless medicine advances in extraordinary ways, this will remain my reality for the rest of my life.

I do not know when it will begin, but at some point, my fingers will feel as if a perverse monster had entrapped tiny living needles inside them. These small, vigorously vicious needles will, before the day ends, try to carve their way out.

Other times, when the needles are dormant, my fingers feel as though an invisible, overweight, and malicious creature is stomping on them. Thankfully, they’re fine most of the time. My daily dose of painkillers helps, but it cannot erase the pain entirely. My physician, an expert on NF, tells me I would not like how I feel with a higher dose. Recently, GLP-1 drugs have helped reduce the pain.

Doctors call this type of pain neuropathy. In this case, it stems from neurofibromatosis 1 (NF), which is caused by a genetic mutation on chromosome 17 (by contrast, a mutation on chromosome 22 causes NF2). Johns Hopkins defines

Neurofibromas as “tumors that grow on nerves in the body”. An analysis of my DNA concluded that a “Pathogenic variant, c.2410del (p.Ala804Leufs*17), was identified in NF1.”

In plain English, my body produces soft, tofu-like masses in places they don’t belong. Some of these touch nerves and cause pain–sometimes only when touched and other times constantly. For some people, fibroma tumors can weigh several kilos and press against key organs. Others may lose their vision or hearing. I suppose in some ways, I am lucky that mine are small, but I have plenty. A few hundred at least.

Perhaps lucky is not the right word. These neurofibromas can be painful or bulky. They’re visible and have made several normal activities difficult—going to the beach, attending a pool party, even changing in locker rooms. I’ve gotten strange looks, and awkward questions, and had three or four dates that ended poorly. When my cousin’s children started growing up, their innocent questions reminded me that I am different

One time, a massage therapist at a spa refused to touch me with her bare hands. During the monkeypox outbreak, some people with NF were harassed.

New kinds of problems can appear at any time. Recently, my fingers began hurting when I swim in pools or the ocean. While I enjoy these activities, I would not do them weekly even if I were healthy. But having something you enjoy become painful is disheartening. My younger years were conditioned–and thus different.

To this day, I frequently wear long sleeves at work or with friends. I hide part of my condition. I hide part of me.

I have had seven or eight surgeries to remove problematic fibromas. After some of them, I looked as if I had been tossed into a blender– cuts and sutures scattered across my body. In 2024, I remember attending a class two days after my latest surgery, with patches on my face, arms, and elsewhere. My professor was excellent, kind, and accommodating, and honestly, going to class made me feel more normal. He told me I did not have to go, but I found comfort in my routines.

I have hundreds of fibromas that cannot all be surgically removed. With no medications available to eliminate them, my only options are symptom management, surgery, and occasional interventions like desiccation.

This mutation, as I’ve come to know all too well, also increases the risk of certain tumors—including gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). NF1 is also associated with intellectual disabilities. My parents recall that my first international school predicted I would never learn English or succeed academically—this was before anyone knew I had NF. Later research confirmed that NF is associated with language impairments (Alivutila et al., 2010). I did not have a disability per se, nor a differentiated curriculum. I have vague memories of working with a language pathologist, a pencil in my mouth to help with pronunciation. Despite those challenges, I enjoyed school. I did well.

From the ICU to the Classroom

During my university years, I discovered joy in teaching. I was pursuing four Bachelor's degrees concurrently and got a gig co-teaching a lab section for an introductory course in Biology. This newly found job pushed me to drop research and thus I moved to studying teaching social studies at Columbia’s Teachers College.

I applied late and was admitted, and they wanted a quick response from me. They even called me. When the phone rang, I was laying in a bed at the ICU at Johns Hopkins. I remember telling them that I would go if I lived and hearing laughter. Then utter silence when they realized I was not joking. Looking back, the program at TC was formidable.

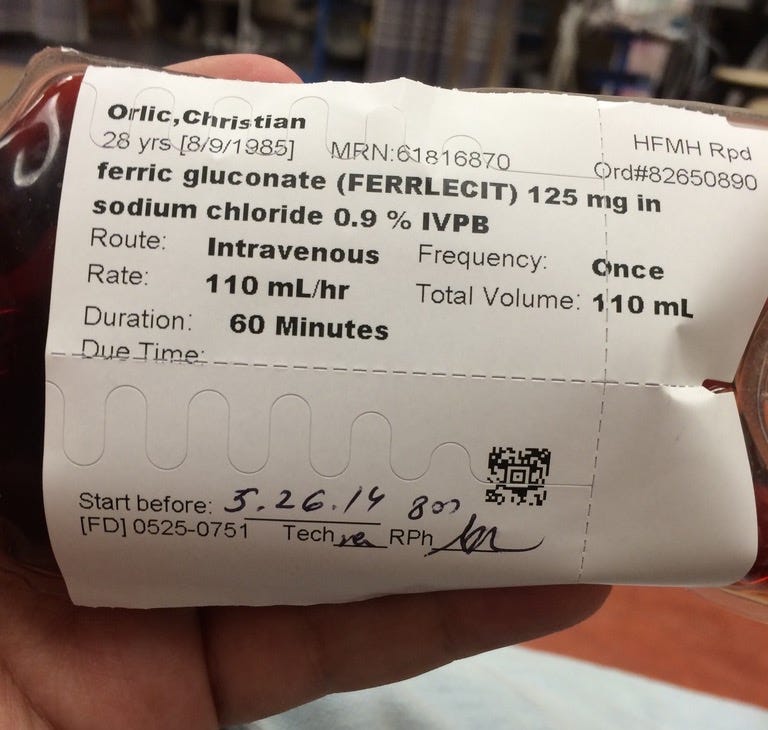

Months earlier, a routine blood exam showed that my hemoglobin was low. After months of tests in several hospitals across two countries and four States, we had not found a cause. The physicians prescribed intravenous iron and it appeared to be helping. Some weeks went by.

It was summer and I flew to see my parents in Florida. One beautiful morning, I was feeling rather tired and my mom said I looked pale. She insisted we should go to the hospital. I vehemently refused saying that I needed a nap. Besides, the World Cup was on and I did not want to miss a game. Reluctantly, I agreed. The nurse came back shocked and told me she had never seen anyone awake with a hemoglobin of four and that I needed blood transfusions immediately.

After a few days of tests and transfusions, the Chief Doctor told me his doctors and him were not good enough. He said that there may be a few people in the world who could save me. We were advised to tell the pilot about my situation if I got dizzy because I could die on the way.

My parents and I rushed to Johns Hopkins where after days of examination and confusion they found a GIST and surgically removed 15 cm of my small intestine. The GIST was a small tumor that, on occasion, caused bleeding which, eventually, would have left me with insufficient hemoglobin to supply my body with oxygen.

By this point, this reads like a story of woe, but however difficult and painful these health challenges have also enriched my work.

The Body as a Blackboard

Both NF and the GIST have positively impacted my teaching, by helping me to connect with my students and transforming a theoretical discussion into an authentic one. Both are part of who I am. After all, we are all embodied beings, and the only way we can learn and feel the world is mediated by our bodies.

When I used to teach biology to Grade 7 and Grade 9, I would tie each of the course’s units to a broader social question. For example, I asked students whether genetic diseases should be eradicated at the start of our genetics unit. Every time, almost every hand went up. Then, I would introduce some of the most dire conditions and a few that are not as bad. Students were even more convinced that we should eradicate these diseases (admittedly that is where I wanted them to be).

During our discussions, I would describe DNA as being a recipe. I would tell my students that answering the questions about genetic diseases required understanding biology – so that is what we would do to converse about the broader question. I hoped that by connecting science to broader questions about the world, students would buy into the course.

I asked students how to make lemonade and students would say mix sugar, water, and limes. I’d reply ah, so I take 1kg of sugar, half a lime, and four drops of water. They would laugh and say no. We would discuss how the proportion of each ingredient and the process can drastically affect the outcome (gene expression). Thus giving students a complex picture before introducing them to a simplified model (Punnett Squares). Near the end of the unit, groups of students would present different genetic conditions and their inheritance patterns. Sometimes, we would watch GATTACA.

Up to this point, I had always worn a long-sleeved shirt and an undershirt. One day I took my dress shirt off revealing a plain t-shirt and my arms sprinkled with many neurofibromas. I'd tell my students I had a genetic disease and that they could ask questions about my condition and experiences.

This revelation made the material studied and the broader questions real, rather than theoretical.

I had, in some ways, primed students to support eliminating such conditions to later undermine this position. The discussion about what to do with people with genetic diseases became authentic. We explored broader questions like what constitutes a disease, and we reflected on traits and behaviors that were once considered diseases but we now see as normal.

This exercise allowed me to exemplify that scientific and technocratic solutions are incredibly appealing, and yet, that these proposed solutions legitimize non-scientific values. For the discussion to work, I had to become vulnerable and within this environment, students could be vulnerable too. Not just about this topic but throughout the course.

In an unexpected turn of events, these challenges helped my teaching. The mutation that almost killed me, gave me NF, and increased the likelihood of GIST became a tool. It took brilliant minds and months of work to figure out what was happening and I could have easily died. In some ways, I think, this helped me see value in doing something I feel was meaningful.

During our study of the digestive systems, I would ask my students if they wanted to hear a story. I tried pretending this was not planned. I wanted them to say yes, because I could use this story as a pedagogical tool to have them revise, without being explicit about what was going on. I find that personal stories—especially those that evoke excitement or concern—can be seamlessly woven into the curriculum.

These stories obliterate the division between theory and life, between the textbook and us.

I spent, maybe half a lesson, telling them about a random blood test that revealed low hemoglobin (an opportunity to revise its function and structure). We would then walk through several of the tests I did. I would mention colonoscopy and endoscopy as ways to visualize the GI tract and their respective journeys (where does the endoscopy start, what does it next encounter, what would you expect to see, etc). I would crack a joke about my conversation with a chair during one of these procedures. We spoke about how double-balloon endoscopy includes a balloon that inflates inside the GI tract, a window to ask students why this may be a good idea (hint: it allows doctors to push out the folds of the intestines so you can get a better view of its surface). They were learning biology, anatomy, physiology, and philosophy of science through what appeared to be an impromptu tangent.

We discussed other tests too. We spoke about barium shakes, nuclear testing, and a test involving swallowing a pill with a camera. In my case, that too suggested there were no problems. We spoke about CT scans and MRI scans.

GISTs usually appear as a shadow on CTs and clearly on MRIs. In my particular case, the CT was inconclusive, and the MRI, like all efforts to find what was causing low hemoglobin, did not point to a cause. Was I distressed? Not really, but after being bedridden for days, I had my parents shave my head because my scalp was unbearably itchy. There seemed no point in being sad or angry so I wasn't.

After the inconclusive MRI; hospital doctors suggested that I should go home and come back for daily checkups. On the other hand, Dr. Robert W Leeper, a young and brilliant surgeon, convinced me that we should operate to see what the inconclusive shadow was (if anything). He found a tumor and cut 15 cm off my jejunum. Several GI specialists never see a GIST in their career (they are that rare). Neurofibromatosis makes it more likely to get them. On the other hand, there are no (and I mean zero) cases of malignant GISTs in NF patients. Thus, I was able to forgo chemotherapy.

Back to my class, this array of tests was a great opportunity to discuss false positives and false negatives. We explored why individuals or societies might use a test with a relatively high false positive test instead of a more reliable but expensive one. I wanted my students to use science to become thoughtful, reflective adults—and here, they could think about how science influences policymaking. They spoke about the role science and medicine should play in such determinations.

I told students that NF also saved me from chemotherapy and reminded them that doctors simply don’t know why this is the case. It was an opportunity to remind them about sickle cell anemia and malaria. More importantly, a reminder that science is a verb—there is still so much left to discover. We also discussed how mutations and genes can have many different effects, and how their desirability may change depending on context (other genes, life history, and environment).

These two health challenges became part of my repertoire.

These experiences allowed me to make the material come alive in ways that would otherwise be challenging. Discussions about false positives, statistical significance, and how scientists know about the world tend to be dry and detached. Suddenly, these conversations were about a real living human being.

Our talks regarding diseases changed when they realized that, to some degree, diseases (or rather the concept of diseases) are socially constructed. They changed when they were not talking about some random person, but when the subject was their teacher. I cared deeply about my students, and by being vulnerable and honest I was able to foster an environment of caring. We bonded and we all benefited from those bonds.

These stories worked because they humanized me, were told with humor and honesty, and invited students to join the journey—something they naturally value in their teachers.

Pedagogically, it worked. The stories kept them interested, tied the material to real life, and allowed me to use tangents as a way to review concepts. They were studying, even when they thought we were just talking.

I always tried to craft lessons that would appeal to everyone. The policy parts might bore some but excite others. The scientific technicalities might fascinate some but lose a few. By combining personal stories, politics, history, philosophy, and science, I tried to get everyone hooked. This multidisciplinary approach was my way of showing that the world isn’t made of separate subjects. It’s one world. Our attempts to divide it are artificial.

These two parts of my life, however disagreeable they may be, brought me closer to my students. NF and my GIST helped me to tear down the walls–between teachers and students, and between theory and life. Blurring these boundaries isn't always easy in traditional classrooms, but I managed to turn these painful experiences into something meaningful and valuable.

Living with NF and Surviving GIST

In other ways, NF and GIST have not been all bad. The GIST nearly killed me, but the NF likely saved me from chemotherapy. That contrast helped me realize that life is shaped by what we choose to focus on1. Since then, I’ve kept a replica of a human skull on my desk—a reminder that life is short, and sometimes shorter than we hope. It helps me focus on what matters and savor moments of joy.

NF is deeply unpleasant and undergoing surgery every few years is far from ideal. I will be needing surgery within the next two years. Currently, I am also contributing to NF research by participating in a study at Johns Hopkins which traces how the condition develops over time.

In March 2025, I found a bit more relief through the use of GLP1 drugs though we do not know why (perhaps some have suggested because they reduce inflammation?).

I am fortunate that I can live more or less a normal life despite my NF. Many people afflicted with this condition aren't as lucky. NF has given me some bad experiences and pain. Yet, I am cheerful. My parents love me dearly and have supported me in all my endeavors. I am partnered, loved, and have found great pleasure in work. I loved working with young adults. I have traveled, taught in different countries, studied, and lived.

If I could wave a wand and make my NF disappear, I would. But I can’t. And there’s no point in dreaming impossible dreams.

I can have other dreams, and I can live those dreams.

I have NF. But I cannot let that define who I am or what I do. I can only transform how I interpret what happens to me, and I am delighted to have been able to use these, albeit painful experiences, to enrich my craft.

There is one thing I know for certain:

Today I will feel pain.

But that is not all that I will feel. I will also laugh, learn, love and, I hope, inspire.

Reading

’s post on Seneca’s views on pain and misfortune helped me, remember this important lesson. Our opinions on all kinds of matters do have a big impact on our experience. Please do read Practice Like a Stoic 41.

Sorry I came so late to this amazing article - I’ve been away & only now catching up on things. I had no idea about this but I’ve got to say, you sound like an excellent teacher. I wish they were all like you, in higher education as well as elsewhere. I’m so sorry to hear about the pain, though. What a thing to have to live with.